|

As part of this project we hope that Indigenous peoples from around the world will tell us their regalia stories and help us to create a space where people can see the living, vibrant Indigenous cultures from around the world through the continued use of regalia. To share your story with us simply do the following: 1) Write a 250-300 word statement for us. Tell us "why is your regalia important to you?" "Where did you get your regalia from?" "What does it mean to wear this regalia?" "Did you make your regalia? What was that like?" You can write this as a short statement, as a poem, as a list or whatever you would like. 2) Include a picture with your submission so we can see the regalia pieces you are talking about. 3) Write a short bio (3-6 sentences) about yourself. Include your name and tribal affiliation. 4) email your submission to [email protected] with the subject: NWC Regalia Story Submission We will let you know when your submission will be posted. It's that simple! We look forward to your stories! Please note the NWC reserves the right to not post entries. Entries may take 6-10 weeks before they are posted. By submitting your story and photo to the NWC you grant them rights and permissions to post your photos, likeness, written statement in its entirety or partially on their website, facebook or other social media sites. The statement and photo become property of the NWC for use. Read the NWC Regalia Stories below!

0 Comments

Photo courtesy of Denise McKenzie Photo courtesy of Denise McKenzie We were awake through the last night of Muriel’s flower dance. Caps and necklaces on, mock orange sticks in hand, we lined up and entered the circular door backwards. I thought, “Don’t bring shame to your family because it’s your first flower dance and you’ve almost crossed the finish line without too many faux-pas.” I stood up straight for my mother and I sang for Muriel. In the morning when this week long endeavor was complete, Muriel, who had been shrouded in the dance pit, emerged with her parents in full dress and beaming. Maybe it was because I was exhausted and it was the first time I was to see this woman, but I thought my heart would explode. My eyes began to well with tears and I kept telling myself “composure, composure.” We stood in line to greet her and I knew that the abalone necklace I had made and worn at her ceremony needed to be with her. The strands of abalone pieces would rustle against beads, and shells, and her body and make a beautiful song. Denise McKenzie (Tolowa, Yurok) is a traditional basket weaver, regalia maker and knitter. She lives in Northern California.

Mary J. Risling (Hupa, Karuk, Yurok) is the Executive Director of the Me'Dil Institute and a traditional regalia maker.

I made my bark skirt with my mom and my aunt Poppy. I made it for my Flower Dance (women’s coming of age ceremony). It was one of the required pieces that I needed for running up and down the river, steaming and other everyday tasks that I did during the ceremony. It was important to me that I learn how to make a bark skirt and not just to have everyone make it for me so that I can pass on that knowledge to people in the future. The skirt is fairly light and a bit scratchy on the legs if you are not wearing spandex. It has distinct swishing noise that it makes when you are running and all the bark pieces hit together. You can also get a bark skirt wet. For example, you can get in the river when you do the bathing as part of the ceremony. This is an important every day kind of dress because you can wear it with most things that you do. Natalie Carpenter (Hupa, Yurok, Karuk) teaches Life Science in San Jose, CA. She is a graduate of Stanford University.

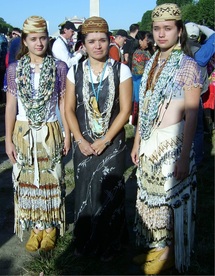

I made my buckskin dress. This represents a lot of hard work for me. A lot of people came together to make this dress and it was a huge accomplishment because we made this dress on a very short timeline. I wore this dress at the end of my Flower Dance ceremony. It was the last day of the dance and I was being presented as a woman, so in a way it represents my womanhood. I can’t really fit it that well anymore because I was very young at the time but the dress was a part of that turning point in my life. I also wore this dress in Washington DC for the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). I wore it again in DC when I won an essay contest and at the awards presentation. My dress has been there for me during these sorts of moments and accomplishments. My dress allows me to present my culture to other people. I wouldn’t say that it is the only piece of culture that I have because I am a very cultural person and I bring my culture with me wherever I am, in my mind and my heart. The dress allows me to communicate my culture in an easy way. When I put on the dress - it’s time to dance, it’s time to sing. The dress has a spirit and life and it aids me in doing these things. At the same time, it’s not the only way to be Native. It helps me; it’s a good part of me but I am this strong, Native woman when I’m wearing it and when I’m wearing work clothes.

Natalie Carpenter (Hupa, Yurok, Karuk) teaches Life Science in San Jose, CA. She is a graduate of Stanford University.

Steve Baldy made my blue jay veil. I picked the colors, I helped with the leather and things like that but it was made for me by Steve Baldy. The veil was a piece that was used in the Flower Dance, the coming of age ceremony, when I was running. Its practical use was to shade my face from view and keep people from seeing me.

To me, the veil represents protection in life. This piece was important to my ceremony and it’s important to me because this ceremony was important to me. At first wearing it I felt kind of goofy. I hadn’t seen the veil much before because the dance was only recently brought back. Wearing it, I remember the little feathers that would flutter in the wind when I was running and they would fly up sometimes. They were also pretty good for shading my face from the sun. My colors were green with blue and I thought it was really pretty. Thinking about it, I remember the actual act of running up and down the river. I remember the ceremonial bathing and the challenges of the dance.  Naishian Richards pictured in her buckskin dress (2014) Naishian Richards pictured in her buckskin dress (2014) My dress was made in the TANF dress making class with Diane James. She did a lot of work on it. I am pretty proud of her and very thankful for it. Making the dress was a process: getting the hide, making the bear grass, getting the materials together and clean. I think the pine nuts were the most difficult. It was neat though because I had my gram, my sister, my brother all working on it. My gram would scrape the black off, my sister would get the rest of the black off cause my gram can’t see that well, and then my brother would grab them and drill holes in them, put them in a pile, and clean them out. It was a cool process because everyone worked on it. And all those pine nuts on that dress are from them and it’s neat because I can look at that dress and “every little tiny pine nut on there came from my family.” The first time I wore it was on the last day of my Flower Dance. That was the day I was coming out and I was being seen for the first time by everyone. It was such a strong feeling... It was like when a butterfly comes out of the cocoon and it’s so beautiful. It felt like that. I felt good about myself . Since that time I’ve worn it almost in every brush dance. It’s pretty cool because when you’re dancing in the Brush Dances you have your own little thing going on and sometimes you can hear your own noise out of all the other girls. I’ve worn it in almost in every brush dance. And I wore it at Sovereigns day for the dress show. I acknowledged all the people that worked on it. I let everyone see it. It’s a lot of work to put together, but it’s worth it. Naishian Richards is Hupa and Shoshone. She lives in Hoopa, CA.

Naishian Richards pictured in her Blue Jay Veil (2014) Naishian Richards pictured in her Blue Jay Veil (2014) My blue jay veil was made by Steve Baldy. It was made to use as a blind that you wear in the Flower Dance ceremony. You put it on so nobody can see you because you are a k’ixinay right now; you’re being put into transition. And it also keeps you in your space. You can’t really see very well, how they have it on you can only see the dirt; you can only see the ground which is good so you can pay attention. Naishian Richards is Hupa and Shoshone. She lives in Hoopa, CA.

Naishian Richards pictured in her bark skirt (2014) Naishian Richards pictured in her bark skirt (2014) I made my bark skirt for my Flower Dance. This was one of the main skirts you wore when you ran, when you had to go down to the river, bathe and pray. I was told that this was a dress for a long time ago that you wore every day. It means that you are wearing something that your ancestors wore. You’re connecting with them in some way because they were doing it and then it still carried on for us to keep doing. My skirt was also pretty tough. It went through sand, it went through dirt, it went through stepping on… but it went through it. I would say my skirt is pretty tough. The method for making the skirt came from Mary Jane Risling. I thought it would be way more complicated. I would have made it so complicated and so hard on myself. But the way she showed me, I thought “I could make this for days.” To gather bark we went up the hill, stripped the bark, peeled it right then and there. And then we started making it and we came up short. So that next day we went up and gathered more bark, but we came up short again! What this did is that my dress has different colored bark on it. It goes dark, light, dark, light. And that is so special to me because you can see the process that we went through. You can see where certain bark started and stopped. And that is not such a bad thing. I think this dance is about making memories and making things that are special to you. I thought it was special how my process went. Everyone worked on it. It just all came together. Naishian Richards is Hupa and Shoshone. She lives in Hoopa, CA.

The thing about maple bark skirts is that they are pretty much made of just the inner bark of maple. This focuses attention on the resource itself and on our relationship with the resource. Maple is fire adapted, a prolific sprouter, and self-pruning (branches not carrying their photosynthetic weight will be discarded by the tree itself). There is great variation among trees. Trees may be multi-trunked, or have a single thick trunk with a deeply furrowed bark. Some are better for stripping than others. I spoke with as many practitioners as I could and tested all the various “rules” for harvesting Maple and found, almost without exception, they didn’t always work. Many factors affect whether bark will peel. The window may be short in hot, drier locations but might extend into late fall in higher, cooler locations. But then, the place that peeled so well last July, just doesn’t the next July. I located only one Karuk story instructing use of maple. But many stories talked about gathering fire wood and about burning logs. Hum, how’d they cut down those trees back in the day? I also know our traditions assigned gathering “rights” to areas, and that maple is very common throughout our traditional territory, including village areas. The more I learned about maple, the clearer it became to me that our system of rights brings with it responsibilities. For example, we use to burn as a means to control insect pests, clear slash, and enhance plant growth in ways that support the health of the plant and the needs of the people. Managing a particular area one would be in relationship with the land and all that lives on it. One would know the plants and animals, weather patterns, and other factors that might impact use of resources. Now days, because many people access the forest, generally only narrow strips of Maple are taken from any one trunk to minimize “damage” to a tree. But what’s better, damaging each truck of a multi-trunked tree, or entirely stripping one of the trunks so the tree will discard it (self-prune), thus delivering firewood? Back in the day, I think I would have let the tree work with me. Mary J. Risling is the founder and Executive Director for the Me'Dil (Maintaining, Enhancing and Defending Indigenous Living) Institute, a nonprofit organization. She is an accomplished regalia maker and owner.  Photo courtesy of Michelle Hernandez Photo courtesy of Michelle Hernandez My dress was created for my coming of age ceremony. When I was 14 years old I was asked what I would like to do for that moment when I would become a young women. Being also from a Mexican heritage I was given the option of a Quinceañera or I could have a sweet 16. Not wanting any of these I asked my family what our tribe did for girls around that age. We turned to our tribe for help. Together we began to research and sought out help from many of the local tribes. Through this process we brought back our tribe’s flower dance. It had been around 100 years since a flower dance had been done in our tribe. Once we figured everything out we began the process of creating my dress. We based my dress off of a very old one that had been stored in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Creating my dress was a wonderful and amazing experience. Through the making of this dress we brought people together. Each part of the dress was created and made by people who cared and loved me very much. These people wanted to help bring me into womanhood and by helping making the dress they got to be a part of that. All the hard work that everyone and I put into the creation of the dress made me have a great appreciation and love for it. This dress is an important part of my life and has shown me the strength that not only I have, but the strength of all Wiyot women. Since my coming of age I have worn my dress for many brush dances and for our tribe's first jump dances, which hadn’t taken place in over 150 years. I look forward to having other girls be able to wear the dress and appreciate the love that was put into it. Michelle Hernandez is a member of the Wiyot Tribe. This fall she will begin attending American University working toward her MFA in Film and Electronic Media.

As long as I can remember, dances have been a part of my life. I was lucky to grow up with family who participated in the dances and could provide me with this knowledge. When I was 9 years old, I started making my very own shell dress. With the help of my mother, grandmother and brother, the process began. We committed every Sunday to working on the dress; from gathering materials to beading strand after strand and sewing them on the dress. I chose purple beads for my dress because it was my favorite color at the time. After my dress was finished, my brother helped me make matching hair ties and necklaces to complete the set. Although this dress is now 15 years old, it continues to dance on young women in ceremony. I enjoy watching my dress dance and it warms my heart when young women ask to wear “the purple dress”. I am thankful to have learned the process of making a dress and look forward to passing on this dress to my daughter as well as helping her in creating her very own dress. Rachel Provolt is a member of the Yurok Tribe.

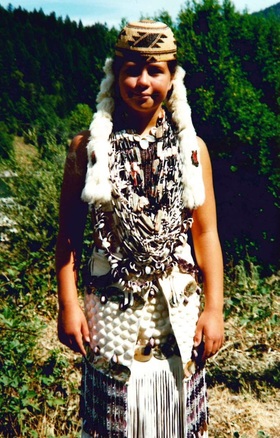

Photo Courtesy of Viola Brooks Photo Courtesy of Viola Brooks Maple bark skirts are made from the inner bark of a maple tree. My mother, Mary Jane Risling, made my skirt. While I have helped her with gathering and assembling maple bark skirts before I didn’t help make this one because I was living in Washington D.C. at the time (too far away to be able to offer assistance). Maple is a strong and resilient tree but there are certain times to gather the bark from certain sized maple. It is critical that a person gather at the right time, at the right place and in a good way to ensure the gathering place is maintained. I have worn this maple bark skirt at other activities, such as a Winnemem Wintu ceremony I attended with my adopted grandmother. I also had the opportunity of wearing a maple bark skirt at the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian. I still wear this maple bark skirt and, as long as I take care of it, I plan to continue to wear it.  At the Gathering of Nations. Photo courtesy of Mary J. Risling (Me'Dil Institute) At the Gathering of Nations. Photo courtesy of Mary J. Risling (Me'Dil Institute) When I was dancing in the 1990’s and early 2000’s I didn’t see any maple bark skirts. I'd heard of them before as what we, women and girls, would have worn 200 plus years ago as our everyday clothes. We’d wear them daily and complete activities like gathering basket materials or weaving. My aunt refers to them as “work skirts” making a clear distinction between maple bark skirts and our ceremonial skirts made from deer hide. The first significant instance, in my mind, when I wore a maple bark skirt was when I was Miss Na:tini-xwe’, AKA, Miss Hoopa Valley. As Miss Na:tini-xwe’ I represented my tribe at various local, regional and national events. I traveled to New Mexico to compete for Miss Indian World at the Gathering of Nations, the largest powwow in North America. I never wanted to be a powwow princess but it did provide me the opportunity to share my culture and traditions and learn about other Tribes. This picture is of me when I wore the maple bark skirt at a grand entry at Gathering of Nations. I was one of the only dancers that had an outfit made out of natural materials from my traditional territory. At Miss Indian World there were events where I was required to sit, travel and do things that were difficult in our ceremonial dresses so I selected to wear a maple bark skirt because it was more practical but still a form of traditional clothing from my area. Viola Chummy Brooks (Hupa/Yurok/Karuk) lives in Sacramento. She continues to participate in ceremonies and dance demonstrations throughout California.

Photo courtesy of Nina Surbaugh-Gibbs Photo courtesy of Nina Surbaugh-Gibbs My first semester at Humboldt State University (HSU) I asked my parents for a basket hat for my graduation gift. I knew graduation day would eventually come and I wanted to proudly walk across the stage, as so many alumni have done before me, in a beautiful and unique basket hat. No one in my immediate family had ever owned a hat or graduated from college. I wanted to proudly represent my family for this occasion. A hat is distinct symbol of pride and beauty and is worn for all occasions. I began to ask community members where to purchase a hat. My mother had begun weaving baskets a short time before, so we put our feelers out to other weavers too. Lois Risling, who is a spiritual adviser to me, suggested I attend the Marin: Art of the Americas Show to look for a hat. It was my last semester at HSU so the pressure was on. I had been looking for a hat for two years and hadn't found a hat that worked so far. I prayed to the universe to help us on our search for my hat. My mother, sister and I made our travel plans and we drove 4 hours south to attend the show. We arrived at the show and I wanted to see everything as fast as I could. I raced through the aisles. I found a few tables selling hats but nothing fit right. I happened upon a woman selling lots of basket hats. They were neatly lining the table and I began trying them on. I didn't know what size I needed but had an idea of a design I liked. I knew when I found it I would know. I really liked a specific hat and it had the design I was looking for. I asked if the seller had any information about the hat and she didn't. Some friends came by and we all chatted about how well the hat fit me. I was nervous about the purchase so I asked the seller if I could go look at myself in the bathroom mirror. She agreed and my mom accompanied me. When I turned to look at myself I began to cry. I knew the hat was mine and she would come home with me. I proudly wore her the day of graduation. I have worn her at Flower Dances, Brushes Dances and in many community events. My hat represents a sense of accomplishment, beauty, grace, and cultural pride. I have bought many hats since then and cherish them. My mother and sister now own their own hats too. We have worn them together on many occasions. Since purchasing this first hat I have learned how important hats are to our culture and how important they are to me. So many things have changed in my life since purchasing my first hat, but I am blessed because she started a path of healing for me and my family. Nina Surbaugh-Gibbs is Yurok and lives in Northern California.

Arya Metter (age 7) in her buckskin dress (2013). Arya Metter (age 7) in her buckskin dress (2013). I wear this dress for dances. I feel happiness when I wear this dress because people made it and it took forever and because it is pretty. When I wear this dress I think about being happy. This dress is for dances like brush dances. At a brush dance you walk around and sing. And you dance by standing tall and going up and down on your feet. I also wore this dress at school. I walked around to show my friends the dress and how to make it and what Indians do. In this picture I am happy and excited. When I dance in front of everyone I am having fun. Being a Hupa person means you dance. When mommy was little she wore this dress to dance and that makes me happy. I really like this dress. It has pine nuts, abalone, and bear grass. I know people who make bear grass braids, like my mommy and my aunties. Someday I will make them too. Arya Mettier (Hupa, Karuk, Yurok) is enrolled in the Hoopa Valley Tribe. She is starting the second grade and likes to swim.

|

About:The Northwest Coast Regalia Stories Project explores the life stories of cultural regalia pieces for Northwest California Native peoples. Read More... Start

About the Dresses California History Native American Women & Regalia Regalia Stories Links & Sources Feedback/ Evaluation Form Archives

August 2016

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed