An Introduction to California Indian History

By Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy & Dr. Beth Rose MIddleton

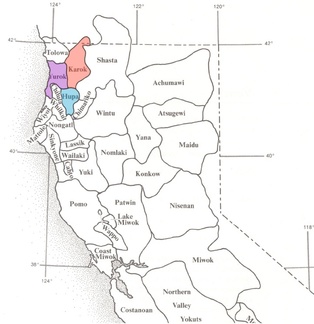

California is home to numerous complex, sustainable indigenous societies with a wide variety of linguistic, cultural, social and political systems. The Native peoples of California have continuously lived and interacted with every part of what is now known as the state of California. As ethnoecologist Dr. M. Kat Anderson writes in Tending the Wild, “Excluding desert and high-elevation areas, it was almost impossible for early Euro-American explorers to go more than a few miles without encountering indigenous people.” She also highlights that “Areas now labeled simply ‘wilderness’ or ‘national park’ on topographic maps once encompassed ancient gathering and hunting sites, burial grounds, work stations, sacred areas, trails, and village sites, all making up what was home to hundreds of generations of California Indians.” “Every place was named,” and those named place names reflect over five language families and 100 distinct languages spoken throughout California. There are more languages families represented in Native California than any other state or region in the United States.

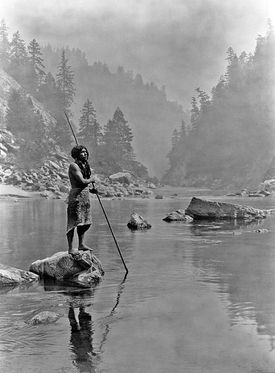

The Hupa, Yurok, Karuk, Wiyot and Tolowa know that they have lived in the area of Northwest California since time immemorial. These Northwest California Indian peoples continue to come together in ceremony and for other community activities. The Hupa, Yurok, Karuk, Wiyot and Tolowa are devoted to their religious and cultural ceremonies, which are not only a means by which they balance the earth, but also how they build a strong, stable society and how they teach values, education, and philosophy to their children. The tribes often come together for ceremonies and travel long distances to attend and participate in ceremonies with each other. This devotion to ceremony and religion has been continuous throughout the long histories of these Northwest California peoples. Despite efforts to annihilate their cultural practices by federal government agencies, missionaries and the State of California, the traditional ceremonies continue. These ceremonies are, in many ways, tools of survival that have helped the tribes to maintain strong connections to the practices and knowledge that have sustained them and their relationships with the area.

The history of settlement and invasion of California was an often violent, destructive experience for the many Indigenous peoples of the region. Scholar Sherburne Cook estimates that the deaths of California Indians between 1770 and 1900 amounted to over 90 percent of the original population. The establishment of the Spanish Missions, the ranching and trading of the Mexican-American war period, and the gold rush all contributed to this depopulation.

Northern California Native Peoples & The Gold Rush:

The influx of Anglo-American settlers in Northern California happened with the Gold Rush in 1849 when many came to California in hopes of striking it rich. In his book Genocide in Northwest California, Hupa scholar Jack Norton, refers to California at this time as a “deranged frontier.” He notes that many newspapers and public postings called for the “annihilation” of Indian people as the only “humanitarian” way of dealing with the population during this time of expansion. Men were often killed outright while women and children were taken prisoner. Many children were sold into slavery. During this period of time California also passed numerous laws that destroyed Indian people, their families and their societies. These included laws that legalized the enslavement of California Indians, laws that gave any white citizen the right to own Indian children, and laws that subsidized a California Volunteer Militia that carried out the massacre of Indian villages and murder of Indian peoples. In 1851 the State of California paid out nearly $1 million to these "volunteer militias" for the killing of Native people. This history of genocide has had a lasting impact on tribes and communities in the state of California. (Johnston-Dodds)

California Indian History & Salvage Ethnography

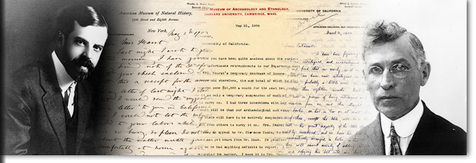

In the early twentieth century following the violent Gold Rush period of California history, many scholars, anthropologists, archaeologists, linguists and others became interested in documenting California Indian culture and life as a means to preserve what they perceived as a “dying culture.” Scholars, including anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, linguists Pliny Earle Goddard and Edward Sapir and photographer Edward Curtis believed that Indian peoples were destined to become “extinct” and that academic “salvage ethnography” would be the only way to document “real” Indian people before they were absorbed by the now dominant Western culture. These scholars worked with numerous tribes to build a portrait of Indian society that existed in the 1830s or 1840s, because they hoped to show what Native life was like before the genocide and attempted destruction of California Indian peoples.

According to many contemporary scholars, Alfred Kroeber was and in many ways still is the single greatest influence on the study of California Indian peoples. Kroeber is a complicated figure in California Indian history and ethnography. Historian Tony Platt writes in his book Grave Matters: Excavating California's Buried Past, that Kroeber “looms biblically large” and is thought of in communities as both a “redeemer” and “nemesis.”

Alfred Kroeber’s Handbook of the Indians of California was published in 1925 and quickly became the primary text used by anthropologists and scholars to study and understand California Indian peoples. One key criticism of Kroeber’s work was that he chose not to write about the policies of genocide against Native peoples in California history. He also believed that “real” Native people were only in the past. Kroeber’s bias and ideas that “real” Native Americans were relics of the past would influence how he understood the continuing cultures of Native peoples during his time. During the early 1900s through the 1930s, Goddard, Sapir, Kroeber and their contemporaries worked tirelessly against what they thought was the eventual extinction of Indian peoples. Kroeber himself believed that there were no “real” or “true” Indians left and that “real” Indians existed in the past, before contact with European settlers. The heyday of ethnographic exploration and documentation declined in the early 1930s during the depression and World War II. Kroeber retired in 1946 and was succeeded by Robert F. Heizer, who was a graduate of Berkeley’s anthropology department and considered himself a specialist in Northwest California Indian tribes.

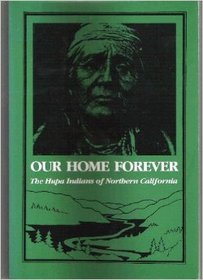

Beginning in the mid-1970s, the American West Center of the University of Utah supported projects with various tribes to create tribal histories. Funding for the projects was provided by the National Endowment of the Humanities. One of the books published as a result of this program was written by Hupa tribal historian Byron Nelson in 1978. Our Home Forever: The Hupa Indians of Northern California was the first comprehensive tribal history written by a tribal member with guidance from tribal elders. These types of tribal histories and the re-writing of history to include stories about the genocide in California became important acts of reclaiming Native American history for California Indian peoples. Related works included memoirs and biographies written by California Indian people, collections of scholarly work, re-interpretation of historical documents and a re-writing of historical analysis, collections and writing of literatures, and theoretical scholarship on the ever changing landscape and communities of California Indian peoples.

The Impact of Salvage Ethnography on California Native Peoples Since early contact with Native peoples, government and educational institutions have amassed vast collections of Native American ceremonial and cultural artifacts. These collections include Indigenous human remains and sacred cultural items. The relationship between Native peoples and those intent on studying them has often been strained because of the lack of respect for and unethical treatment of Native American peoples and their ceremonial and cultural items. Scientific studies of Native peoples, usually completed outside of the community, became the written documentation and history of Native peoples, often leaving out Native voices and stories. The salvage ethnography practiced in the early twentieth century continues to influence how legislators, government leaders, scholars and teachers understand and educate others about California Indians. Anthropologists and archaeologists became the “experts” and “authorities” on Native Americans. They continue to be called upon as expert witnesses and their ideas, theories and “findings” have been given more weight and consideration than those of tribal peoples. “Scientific” designations like “primitive,” “pre-historic” or “hunter-gatherer” created and maintained a particular image of Native peoples and their societies, which in turn affected how the United States justified the atrocities committed against Native people. As Sara-Larus Tolley writes in Quest for Tribal Acknowledgement – California’s Honey Lake Maidus, “Indians battle for their identities through anthropology.” This has real-life effects when it comes to the status of California Indian peoples. Tolley is writing about how anthropology affects the ways in which tribes must now seek acknowledgment and recognition, but the same could be applied to the ways in which tribes must fight for the return of their ancestors from museum collections, or fight to protect or care for sacred spaces.

Contemporary Native Peoples continue to find new ways to tell their own stories. Storytelling has always been an important way for Native people to continue their traditions. As Deborah Miranda declares in her memoir, Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir, that “Story is the most powerful force in the world- in our world, maybe in all worlds.” This is why opportunities to collect these stories and share them are important for helping to represent Native peoples as living, continuous cultures.

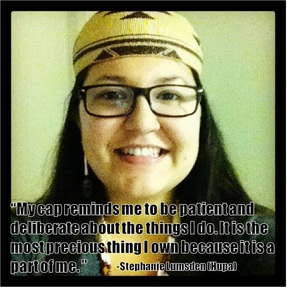

The Northwest Coast Regalia Stories Project

In 2013, the Native Women’s Collective began the “Northwest California Regalia Stories” project. The project explores the life stories of cultural regalia pieces for Northwest California Native peoples. It also examines the history and life stories of Native regalia pieces through the last century. The personal perspectives and experiences of living regalia makers and owners reveal the meanings embedded in the regalia. The traditions that are represented through the collected stories and mixed-media presentations illustrate the remarkable continuance of these cultures. This project engages the Native community in the interpretation and documentation of their own histories and cultures. It collects stories that may otherwise be lost, as many of the elder participants are in their mid-80’s and have not had the opportunity to share these stories. The project is ongoing and will result in a collected archive, exhibition and interactive website that is continuously updated with documentary film shorts, photos essays and stories of regalia pieces from across generations. These stories illustrate how these regalia pieces have their own biographies and are a living example of a vibrant and continuing culture. We look forward to continuing to build this project to include the stories of many other pieces of regalia. If you would like to support the NWC Regalia Stories project so that we can collect further stories of living regalia pieces please donate now. |